Learn You the Web

(for Real This Time)

Once upon a time, the web was just a polite question and an honest answer. A browser asked for a page, a server replied, and that was the whole miracle. The web you use today is still built on that same exchange—it just wears a lot more armor. This book explains how that armor came to be, what purpose it serves, and how you can use it wisely, so hosting and protecting your own corner of the web becomes something you understand, not something you avoid.

Chapters

- Asking for a Page — The web begins when one computer politely asks another for something.

- Getting an Answer — Responses have structure: status, headers, and the content you asked for.

- The Place That Answers — What a web server is, and where the pages live.

- Speaking Clearly — HTTP as the shared language that makes it all work.

- Standing at the Door — Reverse proxies, and why you might want one.

- Locks, Keys, and Quiet Conversations — HTTPS, TLS, and keeping conversations private.

- When Things Get Busy — Load, reliability, and scaling without mysticism.

- Running Your Own Corner — Ownership, responsibility, and the joy of hosting.

Introduction

Before the web became something you scroll, it was something you asked.

Not in the sense of search engines or forms or feeds, but in a much simpler way. One computer asked another computer for a document. The other computer sent it back. That was the whole exchange. If you understand that much, you already understand the most important part of the web.

Everything else came later.

In 1989, at CERN, this simplicity mattered. CERN was, and still is, a place where people from all over the world come together to work on complex ideas. They brought different machines, different operating systems, different ways of storing information. People joined projects, contributed for a while, and then moved on. Their knowledge often stayed behind in files that were hard to find or harder to understand.

Picture a shared office where everyone uses their own filing system. Some label folders carefully. Others scribble notes on loose paper. After a few years, no one quite knows where anything is anymore. Important things still exist—you just can’t reliably find them.

That was the problem.

To address it, Tim Berners-Lee did not propose a grand redesign of computing. He didn’t try to standardize every system or replace them with something new. Instead, he suggested something almost modest to the point of being unremarkable: a way to link documents together, and a simple protocol that any computer could use to ask for one of those documents.

Think of it like writing down clear directions instead of rearranging the entire city.

The result was the web. Not a product. Not a company. Not a platform. Just a shared way of asking for information and receiving it. If two machines followed the same rules, they could talk to each other. If a document existed somewhere, it could point to another document somewhere else. Over time, those links formed a web—not because anyone planned it, but because that is what happens when connections are easy to make.

At its core, the web is still just this exchange. A request goes out. A response comes back. You can imagine it as a letter and a reply, or a knock on a door and someone answering. The rules are simple enough that they can be written down clearly, implemented by anyone, and explained without special equipment or insider knowledge.

That simplicity was not an accident. It was a choice.

Because the web was easy to implement, people tried it. Because it did not require permission, people experimented. Because it was open, people extended it in directions no one had anticipated. A personal homepage, a research archive, a small business site—these were all built on the same basic idea. The web did not care what you were publishing, only that you followed the rules of the conversation.

Success, however, brings new problems.

As more people joined the conversation, new needs appeared. Conversations needed privacy, so encryption was added. Popular sites needed help handling many visitors at once, so intermediaries appeared to spread the load. Some doors needed locks, others needed guards, and some needed someone to politely say, “Not this way.”

These additions were sensible. They solved real problems. In many ways, they made the web safer and more reliable. But they also added layers. And layers have a habit of hiding the simple thing they were built to protect.

Over time, the web began to feel less like a conversation you could join and more like a machine you were expected to use correctly. Hosting a website started to sound like a specialist skill. Words like “infrastructure” and “edge” and “security posture” replaced the earlier, friendlier language of pages and links. The web still worked—but it no longer felt close at hand.

If you’ve ever felt that distance, you’re not alone.

This book is an invitation to step closer again.

We will move slowly and start from the beginning. We will look at what a request actually is, the way you might look at a postcard before thinking about the postal system that delivers it. We will meet web servers as simple, patient programs that answer questions. We will meet reverse proxies as helpful intermediaries—like reception desks or doormen—whose job is to guide traffic, not to dominate it.

Along the way, we’ll use comparisons, small diagrams, and everyday images. Not to oversimplify, but to give your intuition something to hold onto. You don’t need to memorize specifications or learn new tools right away. Understanding comes first. Confidence follows naturally.

The web was built by people trying to make their work easier to share. It grew because that goal resonated with others. Beneath all the layers, it is still doing the same thing it did at the beginning: helping one machine ask another machine for something useful.

Once you see that clearly, the rest stops being intimidating.

Let’s take a breath, start with a single request, and see where it leads.

Chapter 1

Asking for a Page

It’s Not Magic, It’s a Conversation

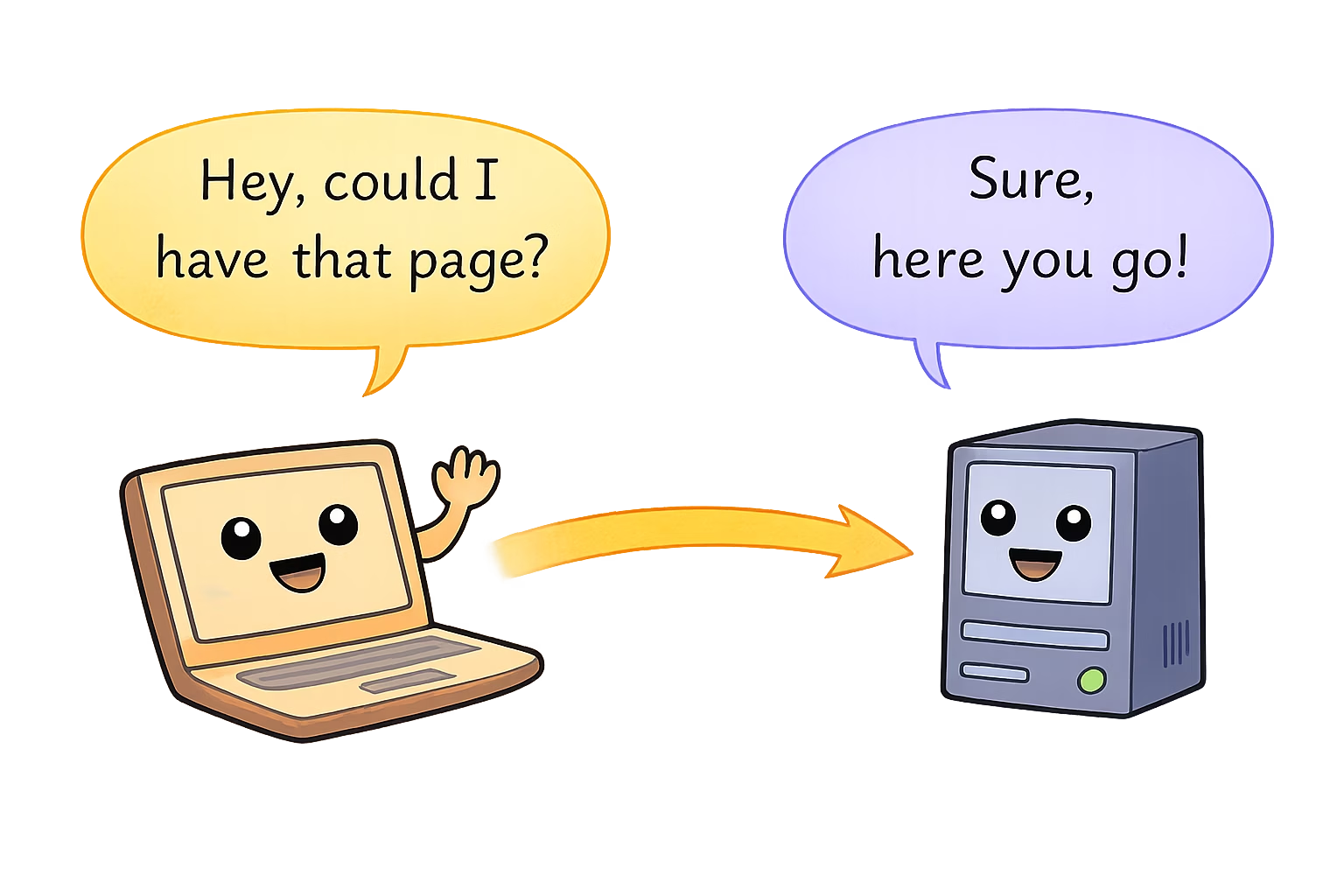

The first thing to understand about the web is that it’s not magic. It might feel like magic when you click a link or type an address and a page pops up instantly, but behind that quick appearance is a simple, structured conversation between two computers. Think of it this way: when you see a new web page load, what really happened is that one computer politely said, “Hey, could I have that page, please?” and another computer responded, “Sure, here it is!” This back-and-forth is the heart of how the web works. It’s less Harry Potter and more like a well-organized phone call or a polite chat at a help desk.

The web is essentially a Q&A session between your device and some remote server. One asks a question, the other gives an answer. No spells, no pixie dust—just computers following a set of polite rules to talk to each other. (That set of rules is a special language we’ll talk about later. No need to worry about it now.) The important thing is: every time you load a page, your device is asking for something and another device is answering. It’s a digital conversation, as ordinary (and as extraordinary) as that.

Now, you might be thinking, “Really? My laptop is having a conversation?” Yes, indeed! Computers aren’t known for their small talk, but when it comes to the web, they follow a strict format of asking and responding—kind of like super polite robots exchanging messages. When you click “Play” on a video or navigate to a new website, your computer (the one in front of you) essentially raises its hand and says, “Excuse me, can I have this information?” The target computer, somewhere out in the world, then replies either with the information (“Certainly, here you go!”) or an apology/excuse (“Sorry, can’t find that.”). And this all happens faster than you can say “World Wide Web.”

So, the web is not some incomprehensible wizardry. It’s more like a well-behaved conversation at a bustling café or a library. To bring this out of the abstract, let’s use a friendly analogy: visiting a library to ask for a book.

A Friendly Analogy: The Library Desk

Imagine walking into your favorite local library (yes, the one with the comfy chairs and the faint smell of old books). You approach the front desk where the librarian sits. The librarian is friendly, but busy—much like a web server handling many requests. You politely ask, “Could I have the book Awesome Adventures of Index.html, please?” The librarian might raise an eyebrow at the quirky title, but they check their catalog, find the book on a shelf, and hand it to you. In web terms, you just made a request and got a response.

[Diagram: A person approaching a help desk and asking for a book titled “index.html”]

Let’s break down this little library scene: • You, the visitor, are like the web browser (say, Chrome or Safari) on your computer. You’re the one with a request, eager to get some information. In the library, you’re looking for a book; on the web, your browser is looking for a web page. • The librarian at the front desk is like the web server. A server is just a computer that stores website data and hands it out when asked. The librarian has access to all the books (information) in that library and knows how to find them. Similarly, a server has all the pages of a website (and related info) stored and can retrieve them when asked. • Your question, “Can I have The Awesome Adventures of Index.html?” is essentially a web request. It’s a structured question. You didn’t just mumble random words to the librarian; you asked for a specific book. Likewise, your browser doesn’t just say “gimme stuff” to a server; it asks for a specific page (often something like “GET /index.html” in computer-speak, meaning “Please give me the main page”). • The act of the librarian finding the book and handing it to you is like the server sending back the web page you asked for. The librarian might have to walk to a certain aisle, locate the book, and bring it back. You might not see all those steps, but they happened. When the server sends a page, it might be doing a bunch of work behind the scenes—looking up files, maybe running some code—but eventually it hands your browser the page data. From your perspective, the book (web page) just appears in your hands (or on your screen).

Notice how civil and structured this exchange is. You didn’t barge in yelling, and the librarian didn’t throw random books at you. There was a clear ask and a clear answer. The web works the same way: a clear ask (request) and a clear answer (response).

In this little story, if the librarian didn’t find the book, they’d come back and say something like, “Sorry, we don’t have that book.” On the web, the server does the same if it can’t find the page — it sends back a message essentially saying “404 Not Found” (which is tech-speak for “I couldn’t find what you asked for, sorry!”). But the tone remains polite: a request was answered, even if the answer is, “Nope, sorry, not available.”

By thinking of the web like this — just a structured question-and-answer session — you demystify a lot of what’s happening. Every website you visit, every cat photo you like, every video you stream, it all starts with one computer asking another for something specific. If the other computer has it, you get the goods. If not, you get an error message (or an apology, if we personify our librarian-server). Simple.

Typing an Address: Your Request’s Formal Invitation

Now let’s connect that library analogy to what actually happens when you sit down at your computer and type in a website address (like www.example.com). Think of the website address (also known as a URL — Uniform Resource Locator, but you don’t have to remember that) as a kind of specific request or even an invitation. It’s like writing down the exact name and location of the book you want on a little slip of paper and handing it to the librarian.

When you type a URL into your browser, you’re essentially telling your browser, “Hey, go ask for this exact thing.” It’s similar to walking up to the librarian and not just saying “I want a book,” but “I want this exact book by this exact author, please.” The more specific you are, the better your chances of getting the right page. The URL is the specificity that guides the request to the right place.

Think of the URL as a street address or a phone number for that website. If you want pizza delivered, you give the restaurant your precise address. If you want a particular web page delivered to your browser, you (or rather, your browser on your behalf) give the internet the precise address of that page. For example, when you enter https://www.example.com/index.html, it’s like saying: “Dear server at www.example.com, could you send me the file named index.html?”

Just like in our library analogy, “index.html” is kind of like the title of the book you’re requesting. Many websites use “index.html” as the name of their homepage (the main page). So in many cases, if you just visit www.example.com, behind the scenes your browser is actually asking for /index.html (even if it doesn’t display that text to you). It’s essentially saying, “Could I have the index page, please?” Often, you don’t see the “index.html” part because web servers will assume you mean the index if you don’t specify something else. But it’s happening, invisibly.

The key point is: by typing a web address, you’re directing your browser to make a very specific request. You’re handing it the equivalent of a filled-out request slip to give to the librarian. Instead of you walking physically to the desk, your browser sends this request through the network to the right server.

How does it know what the “right server” is? Well, that touches on some behind-the-scenes mechanisms (not actual magic, just tech) involving something called DNS that works like a phone book to find the right computer for the job. We’ll explore that in a later chapter. For now, you can imagine that your request is put into a sort of postal system for the internet — the address (URL) ensures it eventually reaches the correct library (server) that has the page you’re asking for.

So when you hit Enter after typing a web address, picture your computer gently lobbing a message into the internet: “Hello, I’m looking for www.example.com/index.html.” That message zips through wires, airwaves, and maybe undersea cables (seriously, across oceans!) until it finds the computer that calls itself www.example.com. When it gets there, that computer hears the knock and starts preparing an answer.

The Web’s Polite Q&A (Step by Step)

Let’s step back and look at this process in a simpler form, without the library metaphor for a moment. At its core, whenever you see something on the web, this is roughly what happened:

1. Step

You ask for something. (Your browser sends a request for a specific page or resource.)

2. Step

Someone hears the question. (A server — a computer somewhere in the world — receives your browser’s request.)

3. Step

The answer is prepared. (The server finds the page or data you asked for. If you’re requesting a homepage, the server will grab that file; if you’re logging in or doing something fancy, the server might do some extra work like checking a database. But fundamentally, it’s getting the answer ready.)

4. Step

You get an answer back. (The server sends the data back to your browser. This data might be the text, images, and other ingredients that make up the web page.)

5. Step

Your browser shows it to you. (Your browser takes the response and displays the page on your screen, assembling all those pieces into something visible and usable.)

That’s it! Five simple steps in a polite exchange.

For example, if you clicked a link to a funny cat video: • Your browser asked: “Could I have the page with the cat video, please?” • The server that has that video said: “Sure, here it is!” and sent the video page (and the video file) back. • Your browser then displayed the page and you got to see the adorable cat do its thing.

This request-and-response dance happens incredibly fast. In fact, it happens many times just to load one page. When you loaded that cat video page, your browser might have actually made several requests: one for the HTML page, more for the images or videos or style files it needs, etc. And each time the server answered. It’s like asking the librarian not just for a book, but also for the accompanying illustrations, and maybe the table of contents separately, and the librarian keeps handing you each piece you ask for. Each ask gets an answer: “Here’s the text, here are the images, here’s the stylesheet,” and so on. Your browser pieces them together into the final page you see.

The cool part is that even though there might be multiple requests, they all follow that same simple pattern: ask politely, get a response. If something fails, the server will let the browser know with an error, but otherwise it’s just answer after answer until the browser has everything it needs to present the page to you.

Peeking Behind the Curtain (But Just a Little)

Now, I know what you might be thinking: “Surely there’s more to it than that? What about all the cables and techy stuff?” It’s true that behind this simple story, there’s a lot of engineering making it happen. The web feels simple when we describe it as just “ask and answer,” and conceptually it is simple. But to make that happen on a global scale, many steps work together seamlessly.

Think of it like our library scene in fast-forward: You asked the librarian for a book. Behind the counter, maybe they quickly checked a computer to see if the book was in their catalog. Maybe they sent an assistant running to the shelves. Perhaps the assistant had to use a ladder to get the book from a high shelf, then hop down and run back. Finally, the librarian handed you the book. You don’t see all those micro-steps, and you might not care how the librarian’s database works or where exactly the book was on the shelf. You just care that you got what you asked for.

Similarly, when your browser asks for a page, behind the curtain: • Your computer has to figure out where to send the request. This involves that DNS thing we mentioned, which is basically like looking up the number of the right “library” to call. It’s as if your browser says, “Hmm, I have this address (URL); let me check the internet’s phonebook to find the exact server’s address (an IP address) to send my request to.” • The request might hop through several other machines on the way. Think of these like postal routing centers or checkpoints. Your data might go through your router at home, then to your Internet Service Provider’s system, then across the country, maybe across the ocean, hitting several network hubs, until it reaches the server. Each hop is like your request letter getting forwarded along the best route to the destination. • There are specific protocols in play — remember, the languages and manners for computers to communicate. The main one your browser and the server use to talk is called HTTP (which stands for HyperText Transfer Protocol, in case you’re curious). Think of HTTP as the grammar and etiquette of the conversation. It’s the reason our computers can be polite to each other — they’ve agreed on how to talk and how to format the questions and answers. (If one computer spoke “HTTP” and the other didn’t understand it, it’d be like someone speaking English to a cow. Lots of mooing confusion.) • The server that receives your request might be one of thousands of machines in a big data center. It has to figure out which file corresponds to “/index.html” or whatever page you asked for. If the site is more complex or your request is for something like search results, the server might actually create the page on the fly, based on what you asked. (For example, if you search for “cute cats” on a site, the server might build a page with cat results just for you at that moment.) But fundamentally, it’s working to prepare the content you requested. • Once the server has the content, it wraps it up in a response (including a little status code at the top, which is like the librarian scribbling “OK” or “Not found” on your request slip). Then it sends the response back through the network, retracing a path back to your computer. • Your browser receives the response and might say, “Ah, I got the HTML page.” Then it looks at that and sees, oh, the page also needs an image and a CSS file (style sheet). So the browser will make additional requests for those items, possibly to the same server, and get those responses too. Only after getting all of these pieces does it finally display the fully assembled page to you.

All of that orchestrates very quickly. The “chain of events” behind one page load can involve dozens of these tiny exchanges, but each one is just a variation of the same polite Q&A theme. At this point, don’t worry if terms like DNS, HTML, or data center sound unfamiliar or intimidating. We’ll introduce those concepts gently in due time. For now, just keep in mind: while there are many steps behind the scenes, the core idea is surprisingly simple — a question and an answer.

In fact, understanding that core makes the more complex stuff easier to digest when we get there. You might eventually learn about IP addresses (like the street numbers of the internet), or how secure connections work (that little padlock icon in your browser address bar), or how your single request can pass through five different countries in a blink of an eye. Those are fascinating topics, and we’ll visit them like tour stops on our journey. But none of those details change the basic mental model: one side asks, the other side replies.

Welcoming You to the Conversation

What’s magical (in a non-magic way) about this realization is that the web stops being an unknowable cloud and starts feeling like something you can grasp. It’s like discovering that behind the curtain, the Great and Powerful Oz is just a friendly old fellow working some levers. In our case, behind the flashy websites and endless content, there’s just a friendly conversation happening over and over, billions of times a day, between machines. And because it’s just a conversation, it means you—yes, you, dear reader—can understand it and even take part in it more deeply if you want to.

Remember how we said this chapter is aimed at beginners but also welcoming to developers? If you’re totally new to this, hopefully now you see that the web isn’t off-limits to you. It’s built on interactions that mirror things you do every day in real life (like asking questions and getting answers). If you’re a developer or a curious techie, you might be nodding along, remembering when you first truly got this concept. It’s fundamental, but it’s also powerful. Many people use the web without ever thinking about what’s happening; you, on the other hand, are pulling back the curtain. Good job!

The beauty of the web is in its simplicity at the core. The complexity comes from scale (millions of servers, billions of users) and layers of improvement (faster responses, secure encryption, fancy visuals). But at the end of the day, it’s still that one request, one response, happening at lightning speed and on a massive scale.

Whenever you navigate to a new page, you can almost imagine your computer and the server as two characters in a story: • Browser (Your Device): “Hello, I’d like to see the latest comic on example-comics.com, please.” • Server (Website’s Computer): “Sure thing, here it is!” (sends back the comic page and images). • Browser: “Got it, thanks! Oh, this page says it needs three images and a stylesheet too – mind sending those?” • Server: “No problem, here they come!” (sends those additional files). • If something’s missing… Server: “Uh oh, I can’t find the image you’re asking for, sorry!” (that would be like a 404 for an image file – perhaps the comic image moved or got deleted).

Even when there’s an issue, it’s communicated as part of the conversation (just an answer that says “didn’t work” instead of “here’s the content”). The browser then can tell you something went wrong, often by showing a little broken image icon or an error message.

Sometimes the conversation can get a bit more involved – for example, if the server wants to verify who you are before giving you something. That’s like the librarian saying, “I can give you this rare book, but I need to see your library card (ID) first.” On the web, that might happen if a page is restricted; the server might ask your browser to prompt you to log in. Still, it’s the same idea: a question (browser asks for page), a conditional reply (server says “hold on, who are you?”), then you provide credentials (browser says “here’s their ID”), and finally the server gives the page. A polite little dance.

What’s Next?

Here in Chapter 1, we wanted to make you comfortable with the idea that the web is nothing more arcane than asking for pages and getting them. You might still have lots of questions (which is great!). For instance, you might wonder: • “How does my request actually find that one server out of all the millions out there on the internet?” • “What exactly does that server’s answer look like? How does my browser turn it into the pretty page I see?” • “What if multiple people ask for the same page at the same time? Can the server handle it? (Spoiler: yes, usually.)” • “What are these http:// or https:// things I see in front of web addresses sometimes? Are those part of the secret conversation language?” • And so on…

Fear not! We will get to all of those. In the chapters ahead, we’ll gently introduce things like addresses (so your request knows where to go), protocols (the fancy word for the languages/rules of these conversations), and the roles of browsers and servers in more detail. We’ll talk about how the internet finds the right computer for www.example.com (hint: it involves something like a global phone book, as we foreshadowed). We’ll also have fun with analogies like postal services, café waiters, or perhaps a team of carrier pigeons (just kidding… probably 🐦). Each layer will build on this core idea from Chapter 1.

For now, give yourself a moment to appreciate what you’ve learned. The next time you load a web page, picture that librarian scenario or the polite handshake between two computers. Imagine the journey of your request as you hit Enter: the little question packet zipping across the globe, reaching the right server, and the answer zooming back. It’s a wild, worldwide journey that happens in milliseconds, yet it’s all built on a simple foundation: asking for a page.

So, take a deep breath, pat yourself on the back for absorbing this concept, and maybe even impress a friend by explaining it in this library metaphor (or make up your own metaphor!). You’re already starting to think like a web insider.

In the next chapter, we’ll start unpacking some of those “behind the scenes” steps we only hinted at here. But we’ll do it gently, layer by layer. For now, just remember: the web is a friendly place once you understand that at its heart, it’s just one polite request and one polite response at a time. It’s like the world’s biggest, fastest Q&A session, and now you’re in on how it works. Not so scary after all, right?

Chapter 2

Getting an Answer

Imagine you’re back at our friendly web library. In Chapter 1, we saw that the Web is essentially a polite conversation: you (the browser) ask the server (the librarian) for a page, say index.html, as nicely as you can. Now it’s the server’s turn to reply. What kind of answer will you get? How does the librarian actually respond to your request? In this chapter, we’ll explore what happens after you ask – how the web server’s answer is structured, and why even a “sorry, no can do” is still part of a friendly exchange.

The Server’s Response: Status and Content

Every response on the Web is a bit like a package with a note attached. The note says what happened (this is the status), and the package contains the thing you asked for – or at least some explanation (this is the content). In other words, whenever a server answers a request, it always includes two things: a status code (a short indication of how the request went) and a response body (usually the page or data you wanted, or an error message if things didn’t go as planned). This status code is like the first line of the server’s response, a numeric “headline” that tells your browser whether the request was a success, a failure, a redirect, etc. . And the content is whatever the server delivers as the result – perhaps the HTML of the webpage, or maybe a simple message saying “Oops, not found.”

Think of it this way: if you ask our librarian for the book “index.html”, they might reply with a smile, “200 OK – here is your book.” In that reply, the “200 OK” part is the status note (meaning “Request succeeded!” ), and the actual book they hand you is the content (in this case, the webpage itself). If the request didn’t turn out so well, the librarian might instead give you a different note like “404 Not Found” and perhaps an apology pamphlet explaining the book isn’t available. But either way, you get a structured answer back. The Web is very orderly about this – no matter what you ask for, the server will always respond with a status code and something in the body (even if that something is just a brief message about an error). It’s a lot like a librarian never leaving you in silence: you’ll always get an answer, even if the answer is “sorry, I can’t find that.”

Diagram: The server (librarian) always responds with a status and content. Here “200 OK” is the status code (success), and the book represents the content (the page data) being handed to the reader.

Now, these status codes might sound a bit technical, but they’re really just the Web’s way of being clear and polite. Each status is a number (like 200, 404, 403, 301…) with an official meaning. Under the hood, they’re defined by the HTTP standard (the web’s conversation protocol) – grouped into categories by their first digit  – but you don’t need to memorize any of that right now. The key is: the server’s little note (status) tells your browser what happened to your request, in a concise code that both sides understand. And right after that note, the server includes the actual content: either the page you wanted, or a substitute message if something went wrong or needs to be done differently.

Different Kinds of Answers

Not every question gets the same answer. Sometimes the librarian finds your book; sometimes they can’t. Sometimes the book moved to another shelf, or sometimes you’re not allowed into a certain section of the library. Web servers have a range of such answers ready. In web terms, these come as different status codes in the response. In fact, status codes are grouped into a few big families by number: 2xx codes mean “Success – here you go!”; 3xx codes mean “Heads up – you need to go somewhere else for this” (a redirect); 4xx codes mean “Uh-oh – there was a problem with your request (client side), I can’t give you what you asked” (like asking for a nonexistent or forbidden page); and 5xx codes mean “Sorry – I (the server) messed up or something went wrong on my side” . Don’t worry about the exact numbers – the idea is just that the first digit gives you a rough category of the response. Let’s look at a few common specific answers you’ll encounter on the web, and explain them in our library metaphor: • 200 OK – “Here you go!” 200 OK is the happiest response of all – it means the request was successful and the server is sending the content you asked for . It’s like when you ask the librarian for a book and they smile, grab the book from the shelf, and hand it to you. The librarian might as well be saying, “Yes, we have that. Here it is – enjoy!” Your browser requested a page, and 200 OK means “everything went fine” – the page (or data) is in the response, ready to display. This is the status code you want to see all the time (and usually you won’t even see it explicitly – browsers don’t bother showing a big “200” when things go right, they just show you the content). In short, 200 OK is the web’s way of saying “Request succeeded, content delivered.” • 404 Not Found – “Sorry, we don’t have that book.” A 404 Not Found response means the server could not find what you asked for . Maybe you mistyped the URL, or clicked a broken link – in librarian terms, you asked for a book that isn’t in the catalog (or isn’t where it was expected). The librarian searches the shelves and computer, then shakes their head: “I’m sorry, that book doesn’t exist (at least not here).” On the web, 404 is a very common status code – so common that it’s probably the most famous error on the internet . Websites often even have custom “404 pages” – playful error pages that say things like “Oops, we couldn’t find that page.” But importantly, a 404 isn’t the server being broken; it’s the server successfully telling you “No such thing here.” The status note is 404 (Not Found), and the content is usually an error page explaining that the resource wasn’t found. In our conversation analogy, 404 is the librarian politely apologizing: “We checked, but we don’t have that book.” • 403 Forbidden – “You can’t access this section.” A 403 Forbidden means that the server understood what you’re asking for, but it’s refusing to give it to you . In other words, you’re not allowed to access this resource. This is like when a librarian knows exactly the book you mean but says, “Sorry, you’re not allowed in that archive room” (perhaps it’s a rare manuscript or you need special permission). The difference from a 404 is that the book exists, and the librarian knows it exists, but you don’t have the right library pass or credentials to get it. The web server is essentially saying, “I see your request, but I won’t fulfill it because you don’t have permission.” Just like a “Employees Only” or “Members Only” sign in a library or club, the 403 Forbidden status is there to enforce restrictions. It’s still a polite answer – think of it as the librarian gently but firmly saying “I’m not allowed to give you that one.” The response will typically include a simple “403 Forbidden” error page (content) telling you that you can’t access that page. Time to check if you need to log in, or if you have the right URL! • 301 Moved Permanently – “That book has moved to another shelf.” A 301 Moved Permanently response means the resource you asked for isn’t here anymore – it’s been moved to a new address (URL) permanently . But don’t worry, the server will usually tell your browser where to find it next. In our library scene, imagine asking for a book, and the librarian responds with, “Ah, that book has moved to another section – let me redirect you to its new location.” They might even walk you to the new shelf where the book now resides. On the web, a 301 status comes with a new Location (the new URL) in the response. Your browser will typically say “Oh, it moved!” and automatically follow the new address to get the content. In everyday terms, it’s like a change-of-address notice. For example, if a website reorganizes its pages, it might send 301 redirects so that anyone asking for the old URL gets sent to the correct new URL. The important part is that 301 tells the browser (and search engines) “This page is now somewhere else, permanently – use the new address from now on.” It’s the web’s equivalent of the librarian saying, “That book lives on shelf 7B now instead of 3A; next time, just go straight to 7B.” The response’s status is 301, and the content is often just empty or a brief note, since the real content will be at the new location. Your browser’s already hurrying off to fetch the right page at the new URL.

Those are some of the most common responses you’ll encounter: “OK, here it is”, “Not found”, “Forbidden”, or “Moved elsewhere.” There are of course many other status codes (the web has a whole zoo of them ), but you don’t need to learn them all now. The key thing to understand is that for any request you send, the server will send back one of these structured answers to let you know how it went. If it’s all good, you get the content. If something went wrong or needs special handling, you get a code and a message explaining why or what to do next.

Diagram: Different kinds of server responses in our library analogy. Top-left: 200 OK – The librarian finds the book and gives it to the reader (success). Top-right: 404 Not Found – The librarian shrugs apologetically, holding a “not found” note (the book isn’t in the library). Bottom-left: 403 Forbidden – The librarian stands in front of a “Staff Only” door, denying access (the reader isn’t allowed in that section). Bottom-right: 301 Moved Permanently – The librarian points the reader towards a different shelf or room (the book has moved to a new location). Each response includes a status (librarian’s note) and possibly content or instructions for what to do next.

Even a “No” is Still an Answer

It’s important (and kind of comforting) to realize that even when you get an error like a 404 or 403, the Web is still doing its job. These codes might seem like the internet equivalent of a door slamming, but really they’re more like a polite head shake. The server didn’t crash or ignore you – it answered you very deliberately, saying “I heard you, but here’s why I can’t give you that.” In other words, even errors are part of the conversation, not the end of it. A 404 Not Found page is the server’s way of politely saying it can’t find something – it’s a useful answer that triggers you to check your URL or search for the correct page. A 403 Forbidden is the server saying “I see what you want, but you’re not authorized,” which might prompt you to log in or contact an admin. These responses might not be what you hoped for, but they’re informative. They’re keeping the dialogue going, telling your browser (and you) what to do next (perhaps try a different page, double-check the address, or come back later).

Even the dreaded 500 Internal Server Error – which indicates something went wrong on the server’s side – is essentially the server admitting, “I messed up while trying to process your request” . It’s like the librarian saying, “I tried to get your book, but the ladder broke and I can’t reach it right now.” Sure, a 500 error is a bit of a failure on the server’s part, but it’s still a meaningful response. The server at least tells you it encountered an unexpected problem (rather than leaving you wondering why nothing happened). In our library metaphor, that might be the librarian coming back looking frazzled and saying, “I’m sorry, I can’t get that book due to an internal issue.” You didn’t get your book, but you got an explanation.

So, errors aren’t the Web being rude – they’re the Web being honest. This structured honesty is part of what makes the web logical and human-friendly. It’s logical because every request gets a predictable form of reply (a status code and content, no silent failures), and it’s human at heart because these replies map to the same kinds of outcomes we expect in real life (yes, no, not allowed, try elsewhere, come back later, etc.). In fact, some error codes even show the web’s sense of humor – there’s an official HTTP status code 418 that literally says “I’m a teapot” (an old April Fools’ joke in the HTTP standard) . It’s not commonly used, but it goes to show that even the protocols of the internet have a bit of whimsy.

By now, you should feel a little more at home with the idea of server responses. You ask a question, you get an answer – and those answers have names and numbers. The next time you see a 404 Not Found page, you’ll know it’s not just the computer throwing a tantrum; it’s the server politely letting you know the book you wanted isn’t on the shelf. And when things work (the vast majority of the time, hopefully), there’s a 200 OK quietly doing its job behind the scenes, saying “All good, sending the page now.”

To recap this friendly conversation: • You (browser): “Hello, could I get index.html please?” • Server (librarian): “Sure, here it is!” (That’s a 200 OK with the page content.)

Or in other scenarios: • You: “Hello, can I get missing-page.html?” • Server: “Hmm, I’m sorry, I don’t have that one.” (That’s a 404 Not Found error page, telling you the page isn’t found.) • You: “Hi, can I see secret-files.pdf?” • Server: “I know what you’re looking for, but you’re not allowed to see it.” (403 Forbidden, access denied.) • You: “Could I get old-page.html?” • Server: “We moved that book to a new shelf – follow me to the new location.” (301 Moved Permanently, with a redirect to new-page.html.)

Each response, even the “negative” ones, has a purpose and content. The web’s request-response system is designed to be robust: whatever happens, you get something back. It’s like having a conversation with someone who will always reply, even if the reply is just “I don’t know that” or “I can’t tell you that.” This means as a web user (or developer), you can always reason about what’s going on. If a page isn’t loading, the status code can tell you why. It’s a bit of built-in transparency.

As we move forward, keep this in mind: the Web is polite and structured. Now you’ve seen how the “answer” part of the dialogue works at a high level. In the next chapters, we’ll peel back another layer of how these requests and responses actually travel (hint: there’s more to those messages, like headers, and there’s something called HTTP making it all possible). But for now, give yourself a high-five – you’ve learned to recognize the web’s answers. From the satisfying 200s to the infamous 404s, you’re starting to speak the Web’s language of responses. And it wasn’t so bad, was it? After all, it’s just librarians and books and a touch of polite internet manners – the Web, for all its cables and code, is still a very human place at heart, where even errors say “hello.”

Chapter 3

The Place That Answers

Metaphor: A library or shop Mental image: “This is where the pages live.”

Key Ideas

Now that the reader understands requests and responses, we zoom out slightly. What is this thing that’s answering?

Core concepts to cover:

-

A server is just a computer that waits

- It’s not a special device — it’s software running on a machine

- Its job: listen for requests, send back responses

- Demystify the word “server” — it serves, like a waiter or a librarian

-

Files on a shelf

- At its simplest, a web server is a program that knows where files live

- When you ask for

/about.html, it finds that file and sends it back - This is called “static” serving — the files don’t change based on who asks

-

The server as a patient shopkeeper

- Open for business, waiting for visitors

- Doesn’t reach out to you — you have to come to it

- Many customers can visit at once, each gets their own response

-

Where do servers live?

- Your laptop can be a server (locally)

- Data centers: warehouses full of servers

- The “cloud” is just someone else’s computer — demystify the term

-

What a server doesn’t do

- It doesn’t display pages (that’s the browser’s job)

- It doesn’t know who you are unless you tell it

- It doesn’t remember previous requests by default (statelessness — light touch)

Tone for this chapter

Warm and grounding. The server should feel accessible — something anyone could run if they wanted to. The metaphor of a small shop or library works well. Not a fortress, not a mystery — just a place.

Bridge to Chapter 4

We’ve met the browser (the asker), the server (the answerer), and seen the exchange. But how do they understand each other? That’s HTTP — the shared language.

Status: Work in progress

Chapter 4

Speaking Clearly

Metaphor: A shared language / ordering from a menu Mental image: “We both know how this conversation works.”

Key Ideas

This chapter reveals HTTP — not as a scary acronym, but as the agreement that makes web conversations possible.

Core concepts to cover:

-

Protocols are just agreements

- Two strangers can communicate if they agree on the rules

- HTTP is the rulebook for web conversations

- It defines how to ask, how to answer, and what to include

-

Why boring rules are powerful

- Because everyone follows the same format, any browser can talk to any server

- This universality is why the web scaled

- Contrast with proprietary systems that only work with their own tools

-

The anatomy of an HTTP request

- Method: what you want to do (GET = “give me”, POST = “take this”)

- Path: what you’re asking for (

/index.html) - Headers: extra context (who you are, what you accept)

- Body: sometimes you send data too (forms, uploads)

-

The anatomy of an HTTP response

- Status line: success or failure

- Headers: metadata about the response

- Body: the actual content

-

HTTP is text-based (at heart)

- You could, in theory, type an HTTP request by hand

- This transparency is a feature — it’s inspectable, debuggable

- Show a simple example of what a raw request looks like

-

Verbs have meaning

- GET: retrieve (safe, repeatable)

- POST: submit (might change things)

- PUT, DELETE, PATCH: other intentions

- The verb tells the server your intent before it even reads the rest

Tone for this chapter

Matter-of-fact but appreciative. HTTP isn’t glamorous, but its simplicity is what made the web possible. Like a well-designed form at a government office — boring, but it works because everyone fills it out the same way.

Bridge to Chapter 5

Now we know how browsers and servers talk. But what if you don’t want every request going straight to your server? What if you want something in between — checking, filtering, routing? That’s where the reverse proxy comes in.

Status: Work in progress

Chapter 5

Standing at the Door

Metaphor: A doorman / receptionist Mental image: “Let me check that for you.”

Key Ideas

This is the pivotal chapter where we introduce the concept of intermediaries — specifically the reverse proxy. This is also where Sentinel naturally fits into the story, though the chapter shouldn’t feel like a pitch.

Core concepts to cover:

-

Not every request should go straight to the server

- Sometimes you want someone at the door first

- Reasons: security, efficiency, routing, inspection

- This isn’t paranoia — it’s practical hospitality

-

What is a reverse proxy?

- A program that receives requests on behalf of the server

- It can decide what to do: pass it through, reject it, modify it, route it

- From the browser’s perspective, the proxy is the server

-

The doorman metaphor

- Visitors arrive at a building; the doorman greets them

- Some are let through immediately

- Some are asked to wait, or turned away

- The doorman doesn’t own the building — they protect and manage access

-

Why you might want one

- Security: block malicious requests before they reach your server

- Load balancing: distribute visitors across multiple servers

- Caching: serve common pages without bothering the server

- TLS termination: handle encryption at the edge (more in Chapter 6)

-

Common reverse proxies

- Nginx, HAProxy, Caddy, Traefik

- Cloud services (Cloudflare, AWS ALB)

- Sentinel — a security-focused reverse proxy for the free web

-

Sentinel’s philosophy (light touch)

- Designed for people who want to protect their own corner of the web

- Not about surveillance — about care

- Fits the theme: understanding your infrastructure, not outsourcing blindly

Tone for this chapter

Welcoming but purposeful. The reverse proxy should feel like a helpful presence, not a barrier. Sentinel should be introduced as one example, not the hero of the story. The reader should understand why this layer exists and feel empowered to use it.

Bridge to Chapter 6

The doorman checks who comes in — but what about eavesdroppers? What about someone listening to the conversation? That’s where encryption matters. Time to talk about HTTPS.

Status: Work in progress

Chapter 6

Locks, Keys, and Quiet Conversations

Metaphor: Envelopes and locked doors Mental image: “Only the right person can read this.”

Key Ideas

This chapter covers HTTPS and TLS — the encryption layer that keeps web conversations private.

Core concepts to cover:

-

HTTP is a postcard

- Anyone who handles it can read it

- The librarian, the mail carrier, the nosy neighbor

- Fine for public information, dangerous for private data

-

HTTPS is a sealed envelope

- The contents are scrambled so only the recipient can read them

- This is what the “S” in HTTPS means: Secure

- That little padlock icon = envelope is sealed

-

TLS: the sealing mechanism

- TLS (Transport Layer Security) wraps HTTP in encryption

- The browser and server agree on a secret before talking

- Anyone intercepting the conversation sees gibberish

-

Certificates: proving you are who you say you are

- A certificate is like an ID card for a server

- Issued by trusted authorities (Certificate Authorities)

- The browser checks the ID before trusting the server

- Let’s Encrypt: free certificates for everyone (mention as democratizing force)

-

The handshake

- Before any content is exchanged, there’s a negotiation

- Both sides agree on how to encrypt

- This happens invisibly, in milliseconds

- Metaphor: two people agreeing on a secret code before writing letters

-

What TLS protects (and what it doesn’t)

- Protects: content of the conversation

- Doesn’t protect: the fact that a conversation happened (metadata)

- Doesn’t verify the intent of the server — just its identity

-

Where does the reverse proxy fit?

- Often handles TLS termination (decrypts at the edge)

- Then passes plain HTTP to the internal server

- Trade-off: simplifies server setup, but requires trust in the proxy

Tone for this chapter

Reassuring but honest. Encryption should feel like a reasonable precaution, not a paranoid necessity. The reader should understand why HTTPS matters without feeling scared about using HTTP locally for development.

Bridge to Chapter 7

We’ve secured the conversation. But what happens when a lot of people show up at once? The library gets crowded. Time to talk about load and scale.

Status: Work in progress

Chapter 7

When Things Get Busy

Metaphor: A busy café or post office Mental image: “More helpers, same rules.”

Key Ideas

This chapter addresses scale — what happens when many people want the same thing at the same time.

Core concepts to cover:

-

One server has limits

- Like one librarian can only help so many people at once

- CPU, memory, network bandwidth — all finite

- At some point, requests start waiting or failing

-

The solution isn’t magic — it’s multiplication

- Run more than one server

- Each handles a portion of the requests

- The rules don’t change, just the number of workers

-

Load balancing: the traffic director

- A load balancer distributes incoming requests across servers

- Round-robin, least connections, or smarter algorithms

- This is often what a reverse proxy does (revisit Chapter 5)

-

Horizontal vs. vertical scaling

- Vertical: make one server bigger (more RAM, faster CPU)

- Horizontal: add more servers

- Horizontal is usually more resilient and cost-effective at scale

-

Caching: answering without asking

- Some responses don’t change often

- Cache them at the edge (CDN, reverse proxy)

- Serve the cached copy instead of bothering the origin server

- Metaphor: photocopying popular books instead of fetching from the archive each time

-

CDNs: servers closer to you

- Content Delivery Networks: copies of your content distributed globally

- When you request a page, you get it from a server nearby

- Faster responses, less load on the origin

-

Resilience: what if one server fails?

- With multiple servers, one can fail and the others continue

- Health checks: the load balancer pings servers to ensure they’re alive

- Graceful degradation vs. total outage

Tone for this chapter

Practical and demystifying. Scale shouldn’t sound like a problem only “big tech” faces. Even small sites benefit from understanding these concepts. The metaphors (café, post office) should keep it grounded.

Bridge to Chapter 8

We’ve covered how the web works at scale. But what about your corner of it? The final chapter brings it back to the reader — running and owning your own piece of the web.

Status: Work in progress

Chapter 8

Running Your Own Corner

Metaphor: Keeping a small shop Mental image: “It doesn’t have to be big to be real.”

Key Ideas

The final chapter brings everything back to the reader. This is about ownership, agency, and the quiet joy of running your own piece of the web.

Core concepts to cover:

-

You don’t need permission

- The web was built to be decentralized

- Anyone can run a server, serve pages, join the conversation

- This isn’t nostalgia — it’s still true today

-

What does “hosting” actually mean?

- Having a server that’s reachable on the internet

- Pointing a domain name at it

- Keeping it running and responding

-

The minimal setup

- A small VPS (Virtual Private Server)

- A domain name

- A web server (Nginx, Caddy) or a reverse proxy like Sentinel

- Let’s Encrypt for HTTPS

- That’s it. That’s a real website.

-

Responsibilities of ownership

- Security: keeping your server safe from misuse

- Maintenance: updates, backups, monitoring

- Availability: making sure it stays up

- These aren’t burdens — they’re care

-

Sentinel in context

- If you’re running your own corner, Sentinel can be the doorman

- Security-focused, designed for people who want control

- Not a replacement for understanding — a tool that respects your understanding

-

The free web is worth protecting

- Corporate platforms are convenient but have costs (data, control, dependency)

- Running your own server is an act of independence

- It doesn’t have to be big — a personal site, a blog, a small API

- What matters is that it’s yours

-

You now have the map

- Requests and responses (Chapters 1-2)

- Servers (Chapter 3)

- HTTP (Chapter 4)

- Reverse proxies (Chapter 5)

- Encryption (Chapter 6)

- Scale (Chapter 7)

- And now: your own corner

Tone for this chapter

Empowering and warm. The reader has learned the fundamentals. Now they’re invited to use that knowledge. This isn’t a call to action — it’s a gentle welcome. The web is still open, still simple at its core, and still waiting for them to participate.

Closing

End with a callback to the introduction: the web began as a simple exchange. It still is. Now you understand how it works, and you can decide how much of it you want to own.

Status: Work in progress